The TADL Local History collection has an array of Tin Can Tourist Association (T.C.T.) documents and ephemera. Their connection with Traverse City begins in 1937, when they held their first summer reunion in Traverse City, a tradition they would keep until the 1970s.1 During their reunions, T.C.T. would camp at the fairgrounds (today’s Civic Center). Their annual trailer shows were open to the public and for their members they provided entertainment, food events, and dances.2 The history of the Tin Can Tourists is not just interwoven into the history of tourism in Traverse City, but in the development of camping and the history of transient lifestyles, urbanization, racism, innovation, consumerist culture, and, lastly, shuffleboard.

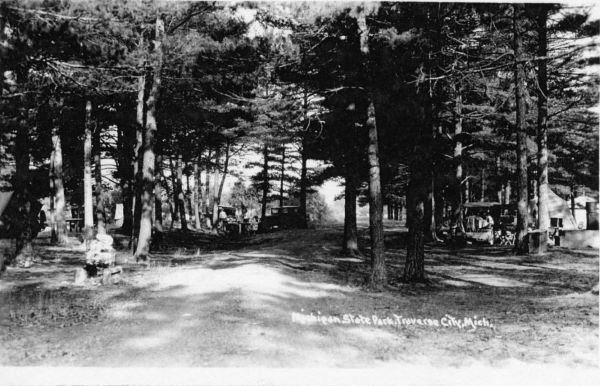

Automobile based tourism was a new phenomenon in the early 1900s and as automobiles became more affordable with the Model T (1908) on the market, cars were facilitating wealthy and middle-class Americans in their touristic endeavors (Figure 1).3 As roads improved and more Americans bought cars, there was an explosion of opportunities for the “auto campers” and “tin can tourists."4

accessed June 20, 2024, https://localhistory.tadl.org/items/show/18216.

However, before World War I there were few public campgrounds. Consequently, automobile tourists had to ask permission to park on private property. As a result, tourist travelers were looked upon and compared to other camping groups (tramps, hoboes, Roma). Under these conditions, the Tin Can Tourist Association was formed in Tampa, Florida in 1919; the name itself started as a joke, referring to “tin lizzie” Model T cars, and the campers’ diet of tin-canned food.5 The association was officially formed in order “to unite fraternally all auto campers, to spread the gospel of cleanliness in all camps, and to help enforce the rules governing all public campgrounds.”6 However, an unwritten motivation for the T.C.T. was to clear up the misconceptions about automobile tourists. The association worked to provide tourist campers with legitimacy and order that would set them apart from minority groups. Even a decade after their first reunion in the city, the T.C.T. was still a topic of debate in Traverse City in 1946. The opinion piece in the Traverse City Record Eagle alludes to the annual reunion in Traverse City, as well as the fraught conception of the tourists: "Unfortunately, a few of the uninformed still think of the Tin Canners as tramps, which they never were…The tin can was the symbol of hoboes for many years and the name reflected unfavorably on the society which selected it."7

The opinion piece is characteristic of the public perception on homeless or “vagrant” groups over the ages. Indeed, this societal response to nomads or “vagrants” predates American history itself (dating back to the Middle Ages) and is a complex social issue far greater than the scope of this research. However, the topic of “tramps” is relevant to the development of camping and is imperative for understanding the groups that the T.C.T. were often compared to in disparaging fashions. What used to mean traveling by foot or as it was used in the Civil War, a “long, tiring, or toilsome walk or march,” “tramp” was transformed into a derogatory word to refer to a vagrant life.8 Among the societal problems because of the Civil War (1861-1865) and industrialization, a considerable population of men were transient workers and/or homeless.

The new labor market of the Gilded Age meant unemployment was a serious threat and reality for the increasing number of people in the employment of others.9 Hoboes and tramps were at the forefront of public consciousness in the 1870s. At this time, the American public placed upon the tramps their fears of the new industrial age and perceived them as a physical confrontation with the new reality -a labor force of instability and devastating poverty.10 Meanwhile, tramps and hoboes themselves faced the same threat of the new economic and labor market -homelessness and dislocation. The idea of “home” was the centerpiece for middle-class perception of social order.11 As such groups of people, who did not share the same definition of a home or had a home, i.e., tramps, hoboes, Native Americans, and Roma, were villainized in the press. It is against this backdrop of longstanding societal disdain of minority groups, the master-less, the itinerant, the nomadic, and the poor that tourist campers found themselves at the turn of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century.

Vital changes came around 1920 when free automobile campsites began to blossom, they were supported by municipal governments to reduce the number of “unregulated auto campers” and unwanted non-tourist campers.12 While battling misconceptions, the group grew tremendously during this time and by 1924, the T.C.T. had over 100,000 members in the United States and Canada.13

The nature of public campgrounds meant two things: the T.C.T. were still not alone in their camping activities and the association felt a new duty to maintain the campgrounds. The T.C.T. aimed to keep these privileges through order and rules of conduct. However, while sharing these woods and lifestyle, the similarities between middle-/upper-class tourist campers and itinerant tramps were still too close for comfort.14 The burgeoning consumerist market had a remedy: abundant, specialized, and stylized camping gear.15 Between 1910-1930 automobile camping moved away from “rough camping” through innovation. Instead of just traveling by car and setting up a camp outside (i.e. traditional automobile camping), automobile camping would evolve into customized Model-T motorhomes, pop-up “tent-trailers,” and finally into recognizable solid body trailers.16 These self-contained, camper-trailers became popular in the 1930s and worked to further distance these tourist travelers farther away from the population of tramps and other camping groups (Figure 2).17 Later in the 1950s, camping and camper-trailers were mainstream and popular. The economy in the 1950s raised the accessibility and popularity of vehicles needed for towing grand, luxurious travel trailers.18 The market for trailers was then consumed by the demand for all the comforts of home like hot and cold water, a bath, a toilet, or refrigerator.19

TADL Local History Collection, accessed June 22, 2024,

https://localhistory.tadl.org/items/show/9919.

T.C.T.’s exclusion of minority groups continued into the 1950s. Included in the Archived in the Local History Collection, the 1953 Tourists Constitution Article III stipulates: “Active membership in the T.C.T. shall be limited to Automobile Camping Tourists of white race and over twelve (12) years of age."20 The policy remined until at least 1967. The group’s policy reflected the racial segregation policies of the American South, where the group was headquartered.21 Additionally, considering the T.C.T.’s preoccupation with their own public image, not challenging the status quo and excluding African Americans was another way to improve their reputation. With accommodation and ethos settled, T.C.T would build upon its affiliations with shuffleboard and Traverse City in the 1950s.

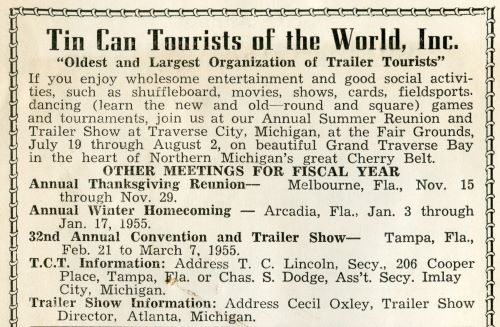

What was once a steamship pastime, shuffleboard landed in Florida as a popular sport in the early twentieth century.22 One of the main attractions was the accessibility of shuffleboard for seniors that were “tired of sitting around and wanting some recreation not too strenuous."23 With shuffleboard as an increasingly popular past time for tourists and people of all ages, the Traverse City Shuffleboard Club began with a bang in June 1930 when 425 people immediately joined the club.24 Eventually built at 801 E. Front Street (today’s Senior Center), the shuffleboard courts and its associated tournaments would remain a highlight for tourist advertising throughout the 1930s as the second largest shuffleboard court in the United State.25 In 1951, the courts were refinished, and the local Shuffleboard Club hosted three major shuffling tournaments: the national tournament, Michigan championship, all States tournament.26 In 1952, the T.C.T. also had their own shuffleboard tournament for members only.27 Additionally for the years 1951, 1953, and 1954, T.C.T. was featured in the Shuffleboard programs advertising to potential members and provide dates for other T.C.T. meetings and reunions (See below)

Both the T.C.T. reunions and the popularity of the shuffleboard were opportunities for local businesses. Located next to the Shuffleboard and Games Club at 731 E. Front Street, Hicks’ Lakeview Inn became Hicks’ Shuffleboard Inn in 1933.28 Later in the 1950s, businesses began to advertise specifically to the T.C.T. (Figure 3).29

TADL Local History Collection, accessed June 27, 2024,

https://localhistory.tadl.org/items/show/30787.

Although the Tin Can Tourists started as an organizational group for the emerging motor-based campers to set a standard for camp life and etiquette, the group continues to be a collection of like-minded individuals with similar interests in camping, Today, the T.C.T. are regaining their numbers, their focus now is the restoration and preservation of vintage or antique campers and camping style. T.C.T. members are centered around vintage and DIY camping, they renovate and transform dilapidated campers into nostalgia on wheels, transporting campers and spectators alike to a different time. History is an important part of the T.C.T. Association, and the group continues the tradition of community, and as a living testament to the collective identity of many Americans.

At Traverse Area District Library Woodmere Branch, there is an exhibit on the T.C.T., camping, and nostalgia in the display case at the top of the stairs during the month of July.

Below:

“The Traverse City Shuffleboard and Games Club Program, 1951,” TADL Local History Collection, accessed June 27, 2024, https://localhistory.tadl.org/items/show/30785.

“Constitution and By-Laws of Tin Can Tourists of the World, Inc., 1953,” TADL Local History Collection, accessed June 27, 2024, https://localhistory.tadl.org/items/show/30792.

[1] “Here July 19 to August 2,” Traverse City Record Eagle, June 3, 1954, 1, Newspaper Archive.

[2] “Trailerites Headed Here,” Traverse City Record Eagle, July 9, 1951, 2, Newspaper Archive.

[3]Terence Young, Heading Out: A History of American Camping (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017), 95.

[4] Young, Heading Out, 95.

[5] “Tin Can Tidbits,” Tin Can Tourists, accessed May 9, 2024, https://tincantourists.com/tin-can-tidbits/.

[6] “Constitution and By-Laws of Tin Can Tourists of the World, Inc., 1953,” TADL Local History Collection, accessed June 27, 2024, https://localhistory.tadl.org/items/show/30792.

[7] “Defending the Tin Canners,” Traverse City Record Eagle, March 27, 1946, 4, Newspaper Archive.

[8] Todd DePastino, Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 5.

[9] Phoebe S. K. Young, Camping Grounds: Public Nature in American Life from the Civil War to the Occupy Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 108-109.

[10] DePastino, Citizen Hobo, 5.

[11] Young, Campaign Grounds, 104; DePastino, Citizen Hobo, 8.

[12] Young, Heading Out, 133.

[13] “Getting Together – The Tin Can Tourists (1919),” Tin Can Tourists, accessed May 6, 2024, https://tincantourists.com/getting-together-the-tin-can-tourists-1919/.

[14] Young, Camping Grounds, 108.

[15] See, “For the Ladies: Trailer Fashion 1937, 1938, 1948 & 1950,” Vintage Trailer Camp (blog), accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.vintagetrailercamp.com/ladies-trailer-fashion-1937-1938-1948-1950.

[16] Young, Heading Out, 212.

[17] Young, Heading Out, 222.

[18] Young, Heading Out, 230.

[19] Young, Heading Out, 230.

[20] “Constitution and By-Laws of Tin Can Tourists of the World, Inc., 1953,” TADL Local History Collection, 10, accessed June 27, 2024, https://localhistory.tadl.org/items/show/30792.

[21] David Michael Burel, “The Comradeship of the Open Road: The Identity and Influence of the Tin Can Tourists of the World on Automobility, Florida, And National Tourism,” MA Thesis, (University of Central Florida, 2012), 100, accessed May 23, 2024, https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2352.

[22] “Shuffleboard is Proving Popular for Rex Terrace,” Traverse City Record Eagle, August 24, 1928, 1, Newspaper Archive.

[23] “Shuffleboard Club Second Largest in the U.S.,” Traverse City Record Eagle, June 30, 1937, 43, Newspaper Archive.

[24] “Vacation Land greets Those Pleasure Bent,” Traverse City Record Eagle, June 30, 1934, 5, Newspaper Archive; “425 Join Traverse City Shuffle Board Club –to Rush Local Courts,” Traverse City Record Eagle, June 28. 1930, 24, Newspaper Archive.

[25] “Happy Days in West Michigan,” Traverse City Record Eagle, June 30, 1934, 17, Newspaper Archive; “Let Us Solve Your Problem…,” Traverse City Record Eagle, June 28, 1938, 15, Newspaper Archive.

[26] “Shuffle Club Season Opens,” Traverse City Record Eagle, June 15, 1951, 15, Newspaper Archive.

[27] “Public Visits Trailer Show,” Traverse City Record eagle, July 28, 1952, 1, Newspaper Archive.

[28] “Shuffleboard Inn Lure for Public,” Traverse City Record Eagle, June 30, 1933, 21, Newspaper Archive.

[29] Independent Grocers, “Welcome to Traverse City Tin Can Tourists!” Traverse City Record Eagle, July 20, 1951, 11, Newspaper Archive; Rennie Oil Company, “Again We Welcome You…Tin Can Tourists,” Traverse City Record Eagle, July 17, 1954, 3, Newspaper Archive.