“No, no, I must live where there are no fires, no nightly alarms.”[1]

In the poem “Quid Romae Faciam” (What will I do at Rome?), the Roman satirical writer, Juvenal (c. 55 CE-128 CE), directed his ire at the excessive conflagrations facing Rome during his lifetime. The constant “horrere incendia” (the horror of fires) described by Juvenal is a shared experience felt by humans for centuries. While fires have always been both the scourge and a tool for the survival for humans, harnessed to a new potential, fires had allowed for rapid urban development and manufacturing in the nineteenth century. Progress and urbanization came with certain dangers and urban conflagrations were a major crisis facing United States communities and cities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[2] While the fire threats in Traverse City in the 1870s was not as great as larger cities (like Philadelphia or New York), the growing town still followed the trend in the second half of the nineteenth century by transitioning to a municipal fire department.[3] With the help of the TADL Local History Collection’s primary source documents about the Traverse City Fire Department, the focus of this article is to examine the development of firefighting in Traverse City in the last quarter of the nineteenth century (c.1877-1901), as well as narrating the major event in Traverse City’s fire history that destroyed fourteen downtown businesses.

With plenty of trees and the thriving lumbering industry, wood was the easiest and cheapest option for construction in nineteenth-century Traverse City. In an environment of closely packed wooden structures, housing businesses and residences alike, fire was not an individual hazard, but a collective one. At this time, with the beginnings of slow urbanization and development of Traverse City, residents of the town may have felt the same “horrere incendia” as Juvenal, and asked themselves, “Quid Urbe Traverse Faciam?”

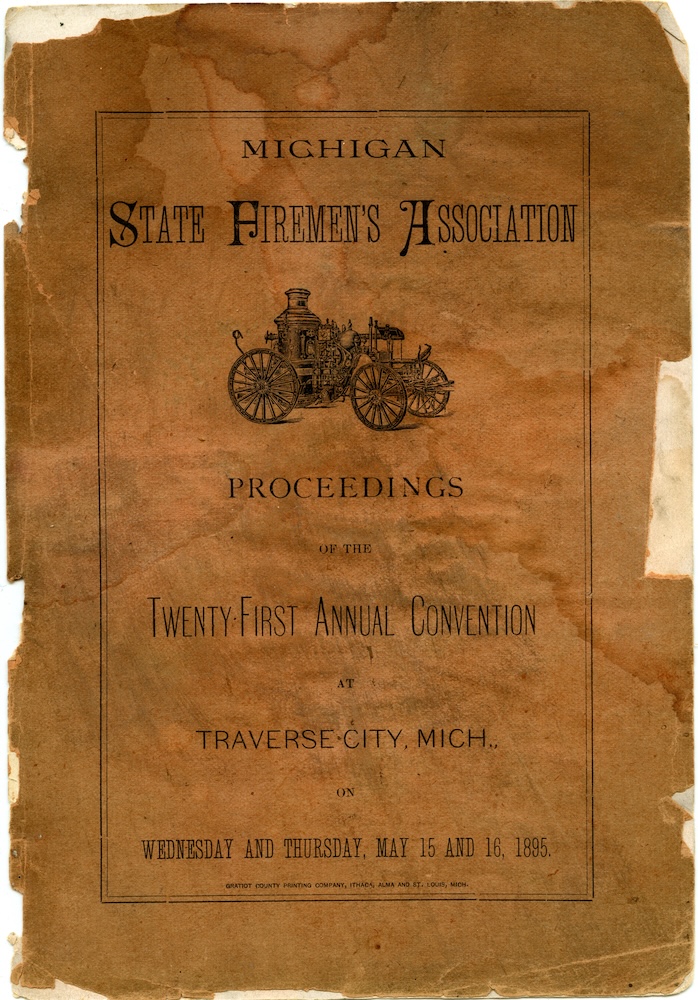

Traverse City had a volunteer citizen led and individually funded firefighting team prior to meeting at Leach’s Hall on March 16, 1877. The meeting, with S. Barnes as chairman, at Leach’s Hall began the transition from citizen led volunteer firefighting efforts to municipally organized fire department with volunteer firefighters.[4] The transformation was not radical, rather many individuals already involved in the firefighting effort stayed on, a few were now employed by the city. This was the beginning of, as discussed at the State Firemen’s Association Convention of 1895, “the trade of firefighting,” which would only progress over the next fifty years.[5] The new career of firefighters began from the work and precedent of the formally community-based fire prevention efforts.[6] Even after the advent of the career firefighters, the Traverse City Morning Record in 1899 stated that the firefighters of Traverse City were “almost exclusively prominent businessmen whose sole purpose is to aid in saving from destruction the property of their neighbors.”[7] The fact that Traverse City relied heavily on the volunteer efforts at times placed safety of the city in a precarious position. For example, in 1897, for the reelection of the longtime fire chief, Charles Despres, the volunteer firefighters threatened to resign if Despres was not reelected by the community council.[8]

The necessity for building codes for fire prevention was realized at the same meeting with the appointment of two fire inspectors, Charles Duprey and John Stevenson, whose duty was to “make a critical examination” of common fire hazards, like chimneys, furnaces, stoves in buildings of stockholders (those funding the fire department) and willing citizens.[9]

With the establishment of a city fire fighting department, the locating committee decided on a single fire house, located on the north side of Front Street (the committee suggested a location directly opposite of Hamilton, Milliken, & Co.) as the most central and best location. [10] The fire house on Front Street was a one-story wooden building, about 30x36 feet in size, with two sliding doors (both eight feet wide), six windows, and a brick chimney. [11] The exterior was boarded with dressed lumber, the building's location on the Boardman River in the rear of the structure was key in the installation of double trap in the floor that would connect with a conduit to river for supplying water to machines.[12] The former engine house on Front Street was no longer in use by 1891, when Julius Steinberg bought the 45 feet front on north side of Front Street where the “old engine house” was located.[13] In May 1890, the Traverse City Common Council resolved $5000 for building place to keep engines, carriages, teams, and fire apparatus of the fire department.[14] The Cass Street Engine House began construction on August 11, 1890.[15] Designed by Architect Hilton, the Engine House was a 34x60 feet two-story brick structure, with the first floor dedicated for the hose carts, hook and ladder truck, etc. and the second floor for use of firemen and council room, along with a basement and a hose tower.[16] The contractors, Hamlin & Johnson, and that mason work done by Sharp & Brigg had almost finished the second story by October 9, 1890. [17]

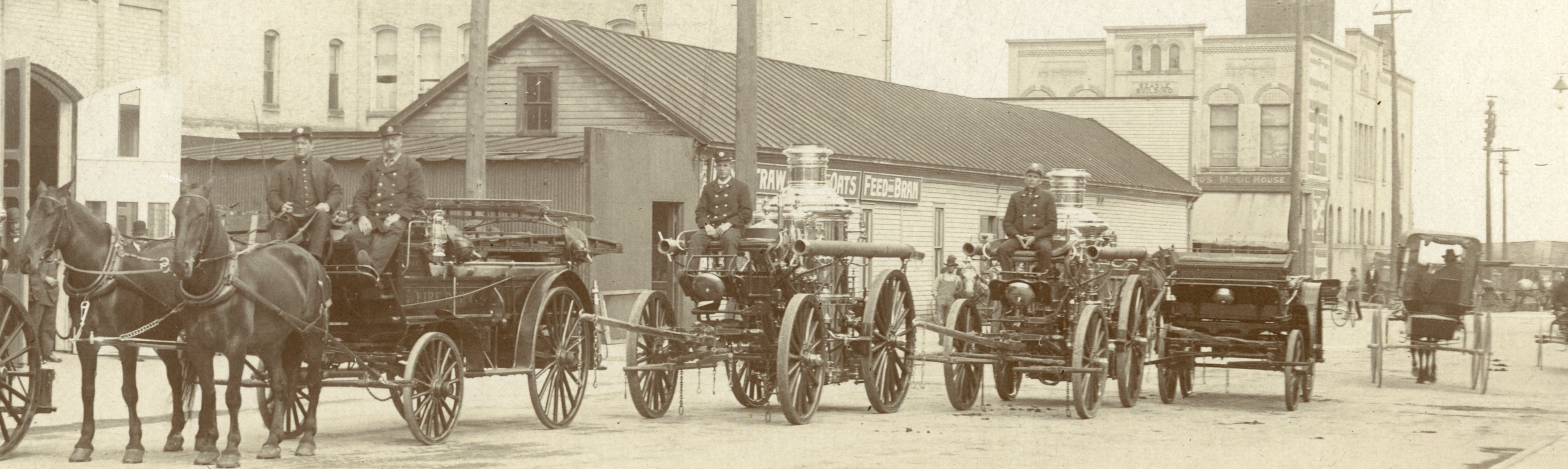

At the beginning, the Traverse City Fire Department consisted of two engine companies, one for each engine in possession of the fire department. These companies consisted of volunteer and paid firefighters, including foremen, engineer, pipemen, and hosemen. The engines, both named by Barnes, purchased in 1877, were called “Wide Awake” and “Invincible."[18] The engines were manufactured by Cowing and Co. and the other Rumsey & Co. Unfortunately, there is a lack of photographs or any known record of the exact models of these initial fire engines.

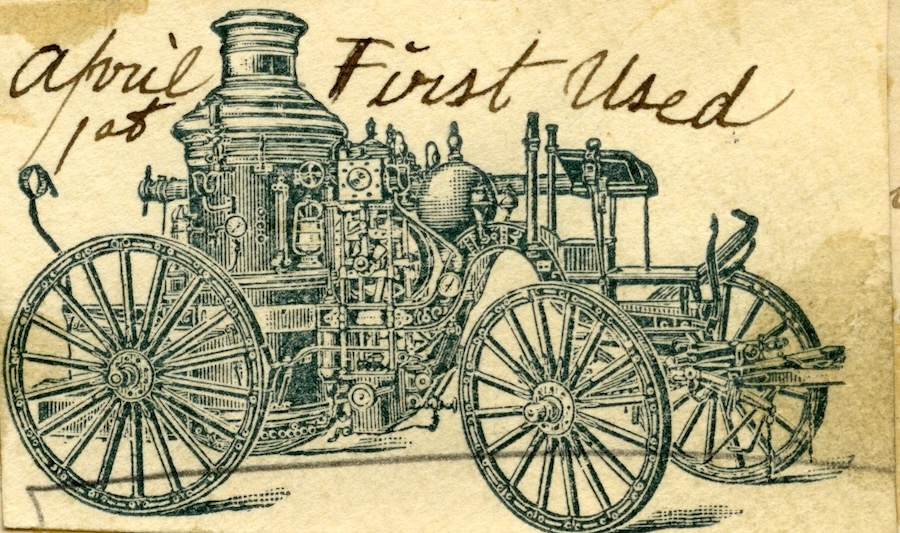

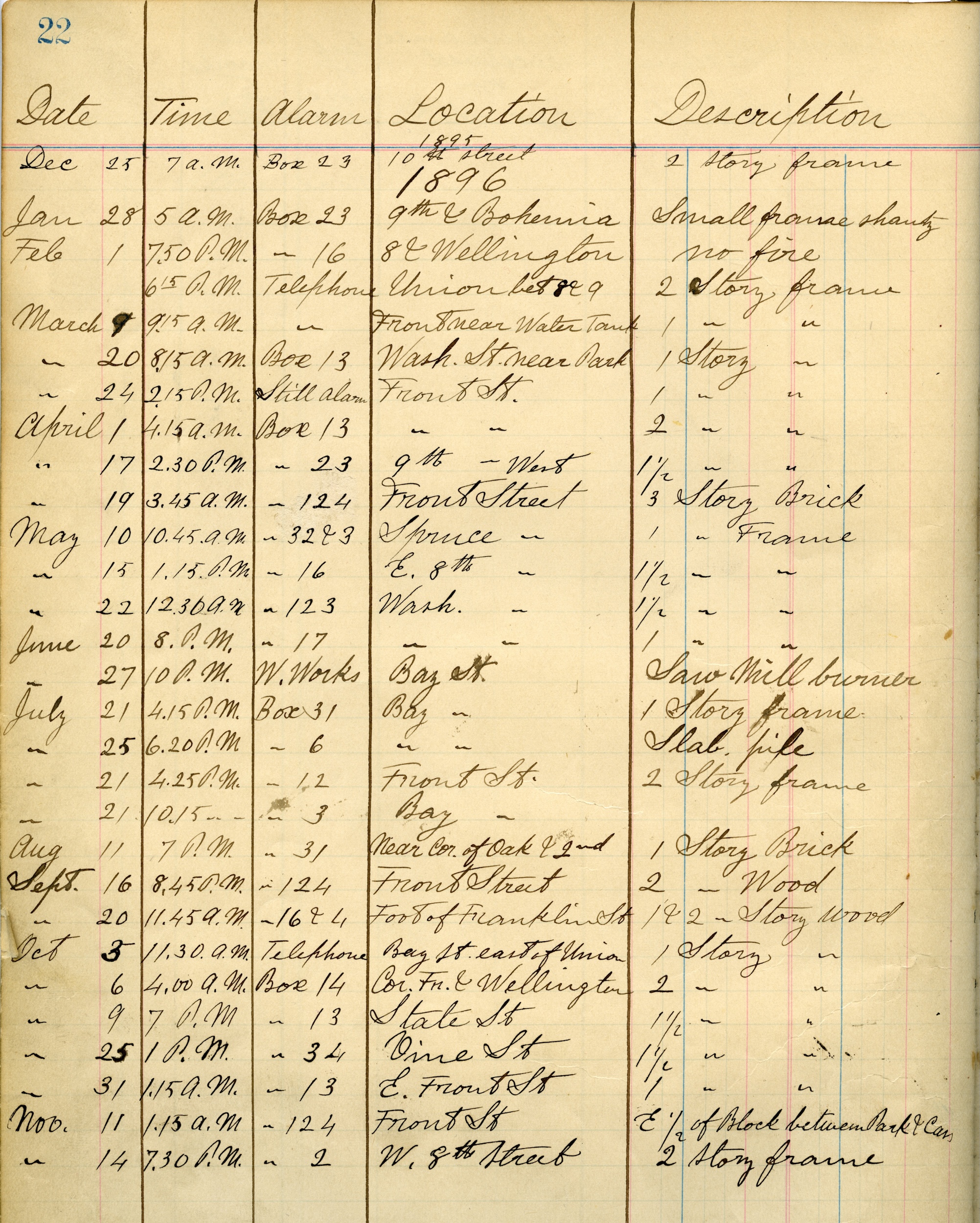

In 1895, the Traverse City Fire Department bought a steam powered, two-piston engine named the Queen City (2378 reg. #), manufactured by the American Fire Engine Company for a total of $3250.[19] The first use of the fire engine was recorded in the Fire Record Book for a conflagration on April 1, 1896, at J.J. Baker’s Saloon on Front Street.[20] J.J. Baker’s plight was petitioned to the City Council on April 7, 1896, in which Baker requested to repair the building (at 252 East Front Street). The repairs were sent to the committee of Fire and Water (at the time consisting of Prokop Kyselka, C.D. Kenyon, A W. Jahraus), under the direction of the chief of fire department.[21] Queen City 1 was replaced in 1917, and now lives in a glass case in front of Michigan Millers Insurance Company in Lansing, Michigan.[22] In 1901 (registration number 2806), a second steam engine, was purchased, named “Queen City 2,” this model had a Fox boiler, operated with a two-piston engine, and was similarly designed with a crane frame and drawn by two horses.[23]

A Hook and Ladder company appears on the city expenditures for the first time November 4, 1895.[24] Hooks were used to pull down partially burned buildings in a controlled manner to extinguish the fire and to prevent the fire from spreading. Those in charge of the hooks, had to know the right places to throw the hook. Firefighters whose job was to man the ladders, had to know where to place the ladder and speed to run up ladder. [25]

Hoses, handpumps, and steam engines, and water were used to extinguish conflagrations for decades before a new method was available to the Traverse City Fire Department. Starting in September 1896, the Fire and Water committee, consisting of Prokop Kyselka, A.W. Jahraus, and W.J. Hobbs, ruled that a chemical engine was “necessary for the protection of property, not only in the city but in the whole city.”[26] More progress on acquiring the engine continues in December 1897, when K. Gibbs, an agent of the Racine Fire Engine Company, proposed to the Common Council the sale of a “No. 30 Special Chemical Engine.”[27] A few months later in March 1898, the Council resolved to purchase a chemical fire engine, for a total of $1125.00 from the Racine Fire Engine Company, a “solid copper double tank carbonic acid gas fire extinguisher of either 35- or 45-gallons capacity.”[28] At the same meeting, the fire department was allowed to purchase two five-gallon fire extinguishers for $25.00 and fire department sell their two three-gallon extinguishers currently owned to the Traverse City Board of Education.[29] After the purchase of a chemical engine, chemicals (often in conjunction with water) were used regularly in 1898 and onwards.[30]

With the Front Street lined with wooden buildings, new fire measures were enacted, including fire alarms. While Traverse City in the nineteenth century was neither the size of Rome nor experienced daily fire alarms, but according to the Traverse City Fire Record and Expense Ledger, 1882-1901, complied by S.C. Despres, chief of the Traverse City Fire Department, false alarms were not unusual. On June 21, 1877, just after the organization of a municipal fire department, the fire commissioners arranged a fire alarm system of wire that would connect the fire alarm signals given to the fire house on Front Street to the “tolling hammer of the [congregational] church bell,” an endeavor that was apparently cheaper than purchasing a bell specifically for the engine house.[31]

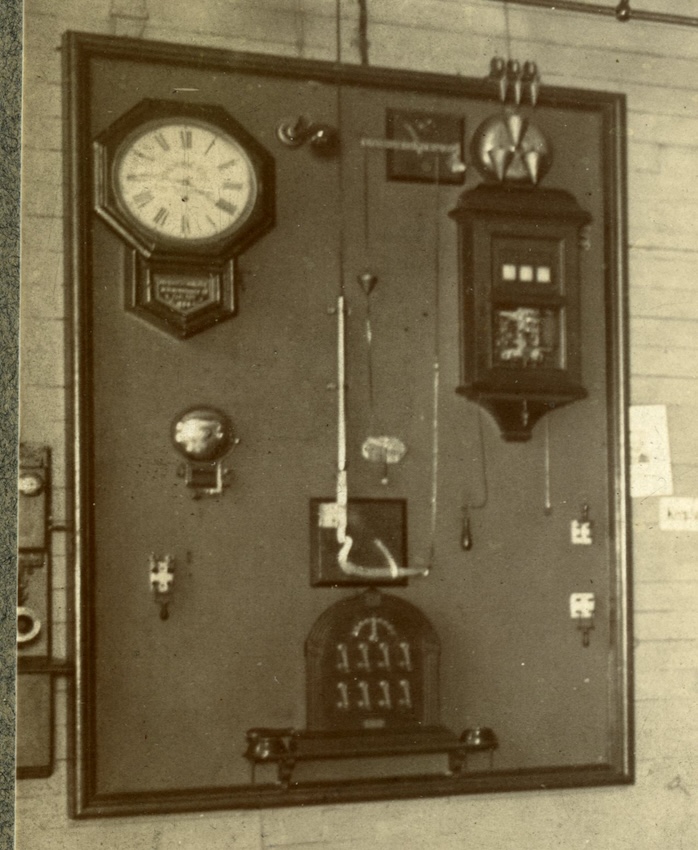

The reliability of the fire alarms proved insufficient, causing the Common Council of Traverse City on June 4, 1883, to instruct the chief of fire department to change the electric fire alarm to avoid false alarms.[32] The need for reparation is especially apparent in the year 1883, in which 4 out of 9 recorded alarms were false.[33] Prior to that according to the Traverse City Fire Record, in the period between 1882-1885, false alarms made up 30-44% of the fire alarms recorded.[34] The problem of false alarms was solved after the Gamewell Fire Alarm system was installed on December 21, 1885.[35] The following three years (1886-1889) showed no record of false alarms (1886-1889).[36] By 1887, Traverse City was but one of the few in the state to have the Gamewell Alarm system installed, and but one of 250 cities in the United States.[37]

The fire alarm boxes remained occasionally problematic, even if false alarms were no longer a constant occurrence. Snow and wind would sometimes inhibit the efficacy of fire prevention in Traverse City. For example, in January 1899, the keyhole of alarm box no. 14, at the corner of Wellington and State Streets, was jammed with snow.[38] Again, on October 10, 1899, fire alarm box #35 was damaged after strong winds, however, Chief Rennie and “Teamster Dunn,” repaired the break in a timely manner.[39]

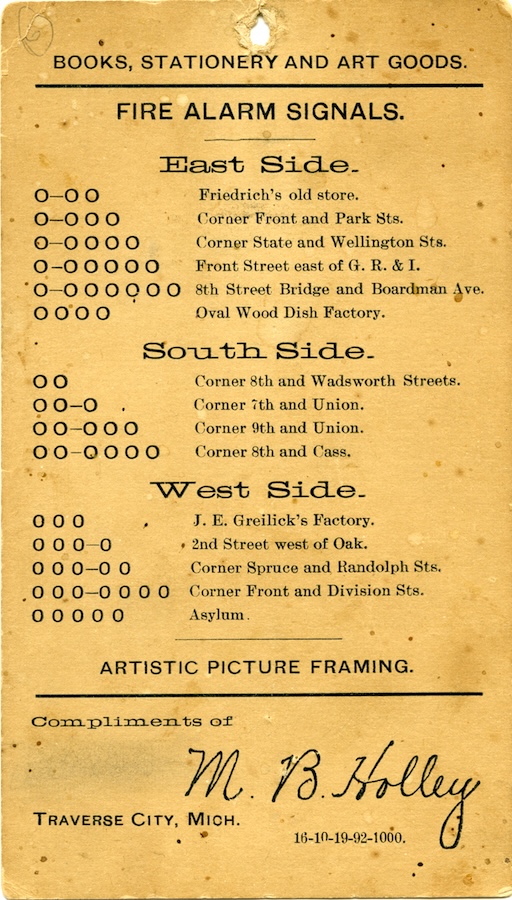

According to the Traverse City Directory 1894, published by F.E. Walker, the first fire alarm is “the long Mocking Bird Whistle,” the next whistles are coded to indicate the location of the fire alarm box which had been pulled.[40] An alarm pulled at box #24 (at the corner of Eighth and Cass Streets) would be two short whistles, a pause, then a successive four blasts. the code as it appears in writing is 00-0000.

The locations of the fire alarm boxes are listed in a few sources. One card, signed by Merrit Bates Holley, locates Traverse City’s “Fire Alarm Signals” subdivided into three districts.[41] According to the information available about the fire alarm boxes, it appears likely that Holley made this card prior to the addition of the box at that Cass Street Engine House (box #6), circa April 20, 1893.[42] However, one cannot rule out the possibility that Holley may have just excluded call box #6 at the fire station and published the card after 1893. The fire alarm box on the corner of Union and Bay Streets, installed sometime after July 1895, is also missing from the card, narrowing the time frame further to sometime after the first evidence of Holley in Traverse City, 1884, and sometime before April 1893 or July 1895.[43]

Fire boxes would continue to be placed at locations around the city. The assets of the fire department as of June 7, 1894, lists a total of 15 boxes of the fire alarm system (worth of $2044).[44] By April 1, 1899, the fire department added to the fire alarm system a total of 7 alarm boxes costing $525.00, using 1125 feet of wire.[45]

Around the turn of the century, more fire boxes were being strategically placed nearby manufacturing plants and factories. In September 1899, a new alarm box was placed in front of the Starch factory on Bay Street, box no. 37, the twenty-seventh fire alarm box in the city.[46] October 13, 1900, at the request of the Committee on Fire and Water (consisting of W.W. Smith, George P. Garrison, and R.W. Round), two fire alarm boxes were approved to be purchased and one box located on east Eight street and Boardman Avenue to be moved to the west end of the Eighth Street bridge, closer to the Fulghum Co.'s plant. The other two boxes were approved to be placed strategically near other factories, one at corner of east Eight and Franklin Streets near the Basket Factory and the other on the corner of Beitner Street and Railroad Avenue, opposite Beitner’s factory.[47] In 1903, another new fire alarm box no. 43 for fire department was placed near South Side Lumber Co’s factory.[48]

S.C. Despres (sometimes referred to as Charles Despres) appears as one of the first Fire Inspectors (Chas. Deprey) of the Traverse City Fire Department appointed in 1877. As of January 1882, Despres was the Fire Warden.[49] Despres was appointed to chief of fire department on April 2, 1883.[50] Despres was the fire chief until he resigned on June 7, 1897. The resignation was dependent on whether the Common Council would follow through with an ordinance decreasing the annual salary of the fire chief from $1000 to $800.[51] At the same council meeting, the members of Traverse City Fire Department petitioned the council to retain services of S.C. Despres as chief. In addition, at the council meeting on June 21, the Committee on Fire and Water reported to the council that “the best interest of the public and of the Fire Department would be served by re-appointment of Chief Despres at a rate of compensation as fixed by the council, believing that the many years experience of our Fire Department more acceptable to our citizens, who have property interests at stake than would the services of the new chief.”[52] The termination of Despres as chief was finalized in July 1897, when the council approved of the removal of fire alarm bell from ex-Fire Chief Despres’ residence and placed into Fire Chief Rennie’s (the newly appointed fire chief) residence.[53]

S. C. Despres was an active member and delegate for the Traverse City Fire department in the State Firemen’s Association for many years. In May 1895, Traverse City not only participated with the State Firemen’s Association, but Traverse City was the location for the annual convention. Every department in the state was entitled to delegates, for Traverse City the delegates were Chief S. C. Despres, E.B. McCoy, Jas. Murchie, Herman Coch.[54]

At the convention, Chief Despres acted as co-host, along with to Perry Hannah, who orated an opening speech. At the end of the first day, May 15, Chief Despres arranged for delegates of the Association to “visit the asylum for insane persons.”[55] Visiting the State Hospital was a regular trip for tourists or hosts wishing to entertain their guests.[56]

James Murphy, State Firemen’s Association's president, while addressing the delegates, reveals the self-conception of what it means to be a “fireman” and the discontent with development in urban governance's approach to implementing fire codes.[57] Murphey attributes casualties of firefighters to unsafe, cheap, tall constructions, while empowering the association to act on the unsafe conditions:

"It is easy to die for one’s country, but when death proceeds in such horrid forms from attempts to save old money bag’s fire-trap, at a salary of forty dollars a month and (if ashes of the dead can be found) a neglected grave, a dependent family. It is time this association breathed into itself the breath of life and entered a more vigorous protest."[58]

Most fires in Traverse City were not necessarily caused by skirting fire codes, rather as recorded in the Traverse City Fire Record, conflagrations in Traverse City were mostly caused by chimneys,[59] sparks from a mill,[60] gasoline stoves, or stove pipes.[61] Records mention a few times in which hot ashes and occurrences of lightning were the sources of fire.[62] Other out of the ordinary, yet almost cliche, fire causes include a man smoking in bed in 1890, [63]“children playing” or “children with matches,”[64] and someone frying pork.[65] The cause for other fires were sometimes ruled as “don’t know” or “unknown.”[66] Many “incendiary” fires occurred as well, including the November 11, 1896, fire.[67]

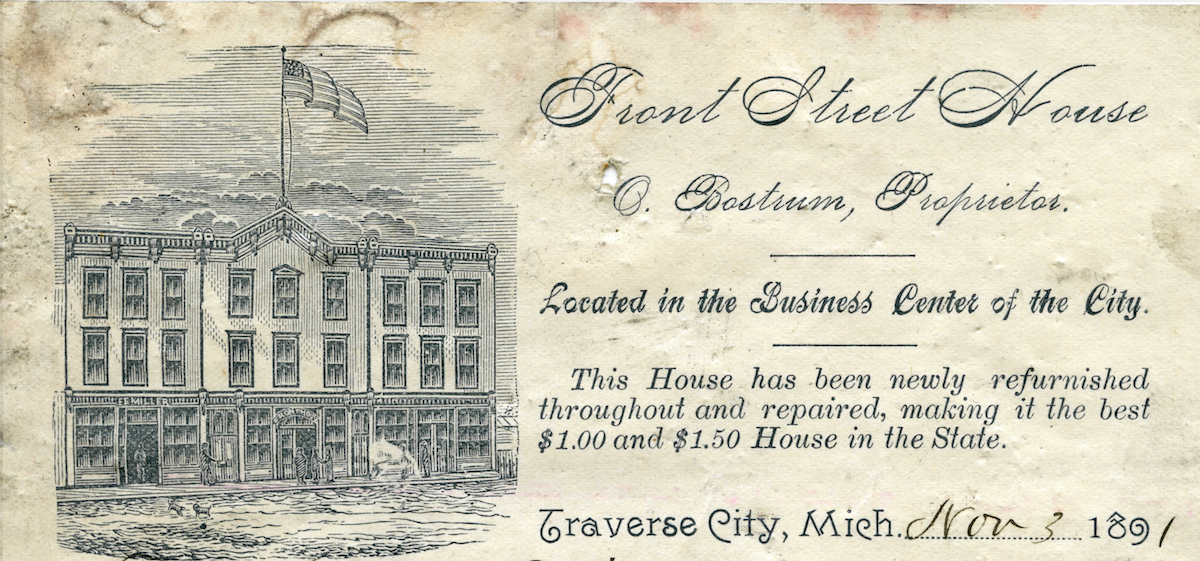

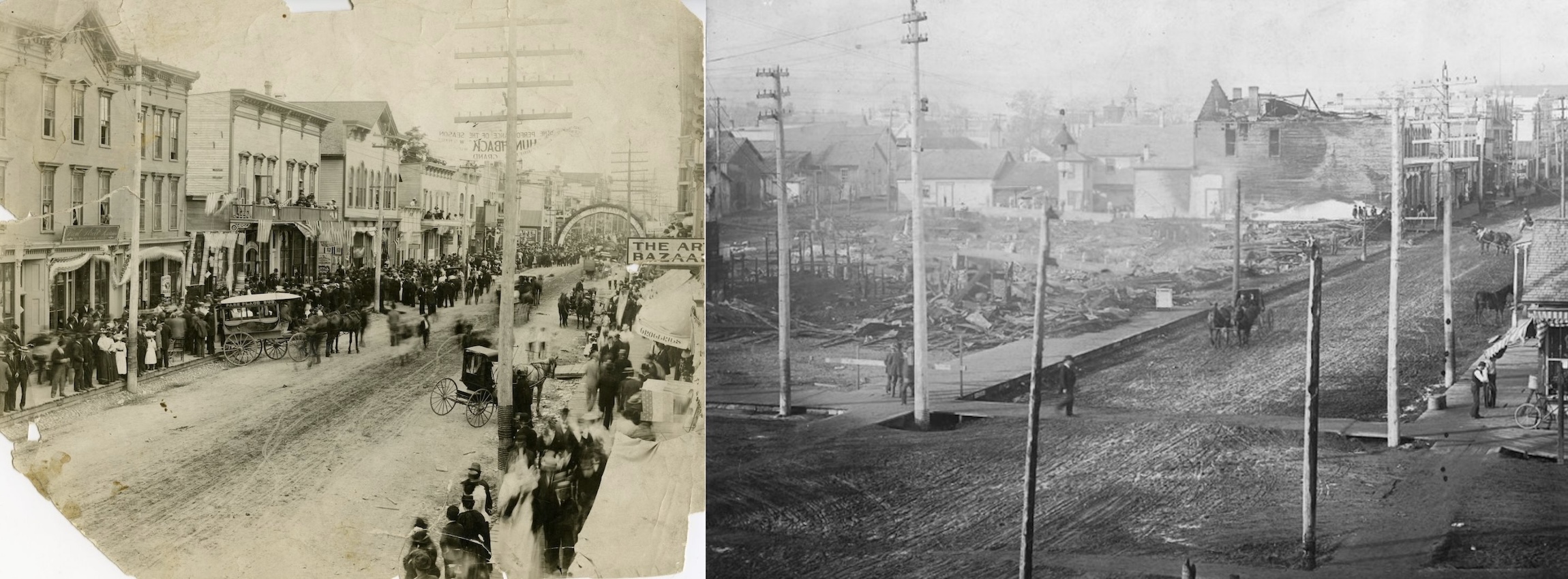

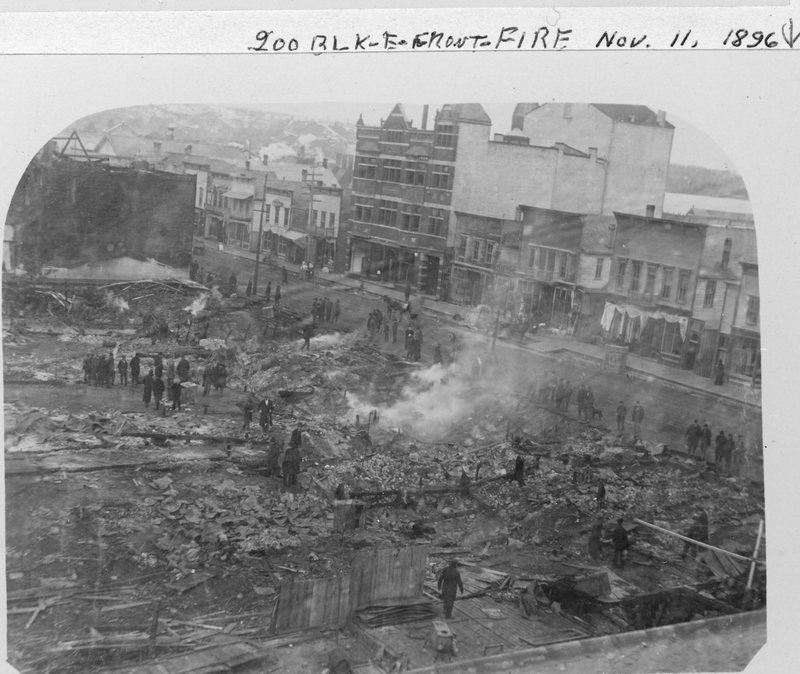

A little over two months after the Oval Dish Factory fire, in which a one- and two- story wooden buildings were badly damaged or destroyed, Traverse City faced the “biggest fire ever had” on Front Street, destroying a total of fourteen businesses on November 11, 1896.[68] The official cause of the fire in the Traverse City Fire Record was “incendiary,” that is arson fires set by individuals on purpose.[69] The State Firemen’s Association’s stance on the topic describes the motivation for arson is the “impassionate desire for excitement, to wreak vengeance, to plunder, and under desperate circumstances to obliterate evidence of murder.”[70] It is unknown who exactly started the fire, but it is possible that the fire’s cause, as reported in the Grand Traverse Herald and other Michigan newspapers, was the result of an accidental chemical fire originating in C. A. Bugbee’s drug store. According to Fire Chief Despres, as told to the Herald, the origin of the fire was impossible to precisely find the origin in the Front Street House or the Bugbee’s Drug Store.[71]

Our most detailed account of the “terrible fire” of Traverse City is from the Grand Traverse Herald. The accuracy of the entire article is difficult to judge since newspaper articles were often sensationalized and augmented with fictional details to entertain the reader. According to the article, the fire was discovered by S.C. Despres, A.E. Waterbury, and the night watchman, Allen Grayson, who at the first signs of fire, were standing just outside the door of the engine house on Cass Street. Despres and Waterbury quickly harnessed the horses and were at the corner of Cass and Front Street by the time Grayson was able to start the alarm. This speediness is in line with other occasions before and after, for example March 13, 1884, the Grand Traverse Herald noted that the Traverse City Fire Department were already in the streets on the way to a fire before the general fire alarm ceased.[72]

At 1:15 AM the fire alarm sounded and the entire fire department including steam engine rushed to the scene of a fire in the rear of Front Street House, the three-story wooden structure on the south side of Front Street.

The fire, that began at the Front Street House hotel crept westward, likely due to the strong wind blowing southwest, burned the eastern half-block of Front Street between Park and Cass Streets.[73] As the fire spread, it destroyed or damaged a total of fourteen businesses,; including the saloon of Peter Bostrum, C.A. Bugbee’s drug store, the Brosch & Sons’ meat market, C.A. Cavis’ Cigar store, H. Cook grocery store, Griffith & Martin barbershop, J.J. Baker’s building, Loren Fuller’s building, the Ellis Building, Rich & Hallberg building, Ransom & Son’s store, Mrs. Daniels’ grocery store, E. C. Stiles, and the dray office of George Jameson. Further occupants' experienced tremendous losses, the families and individuals living above businesses lost almost everything in the fire.[74] On the north side the conflagration damaged a few buildings, primarily the few wooden buildings located between Steinberg’s Grand Opera House and Park Street.

Steinberg’s Grand Opera House, on the other hand. was relatively saved from the “terrible fire.” Julius Steinberg began construction of the three-story brick block known as the “Steinberg Block,” in 1891, after the purchase of an additional 45 feet on Front Street that once belonged to the “old engine house.”[75] The opera house was completed by mid-1892 and revered as “first-class entertainments in a handsome, comfortable perfectly appointed opera hall.”[76] Opera House could not withstand the immense heat of the fire, cracking the plate glass of the Grand Opera House’s facade across the street. The intensity of the fire is expressed by the Herald, describing how with eclectic lights cut off in the city, the blaze colored the snow “a lurid red, and made it light enough to see to read.”[77]

The Grand’s ability to withstand the fire was due to a few factors. First, and perhaps most influential influence was the construction material, since the Steinberg block a brick building with “Vitrified Brick.”[78] The Grand Traverse Herald attributes the most effort to avoid fire was done by Julius Steinberg, his son, Alec, and Steinberg's employees, who were at the scene, working to extinguish any fire caused by embers falling into the wooden window frames and cornices.[79] Lastly, the fire department was said to have prioritized the opera house more than the neighboring wooden buildings. As such, when the fire spread to the north side of Front Street, the streams of water were then aimed at the “more serious danger in the neighborhood of the opera house.”[80]

The exact reasons for this decision to focus water on the opera house instead of the more vulnerable wooden structures could explained by the sheer size of the Opera House Block. According to the Herald, the fire department saw the wooden buildings as hopeless, “little could be done to save them” and judged that the opera house as an important feature of Front Street and of the community, that its survival was a priority over the wooden buildings.[81] Additionally, to stop the fire at the Steinberg’s Grand meant the fire would not progress further west along the north side of Front Street.

In the end, fourteen buildings, which housed businesses and in the upper stories, homes for individuals and families, now lay in the charred ruins. The half block that met a less catastrophic fate on the north side of Front Street, they were scorched and blackened, but image of Steinberg’s fire damaged Opera House was also devastating, “Saddest spectacle made by the dilapidated and scarred windowless front of Steinberg’s Grand.”[82] The next day, various businesses had to find an intermediary location, F. Brosch‘s meat market and Mrs. E. M. Daniel’s grocery store arranged stock on the north side of Front Street on either side of the Grand Opera House. While Ransom & Son opened for business right where they were, although they were literally “without a roof over their heads.”[83] One fatality was reported, that of the thirty-four-year-old porter at the Front Street House, Ed. Newberry.[84] The fire department found the charred remains the morning after which they identified as a human body and a body of Newberry’s dog at his side.[85] A total of thirty guests and employees at the Front Street House, escaped through the windows in their night clothes, they were then boarded at the Park Place Hotel.[86]

The Great Fire of November 1896 involved not only the experiences of business owners and hotel guests, but also the fire department. The Grand Traverse Herald narrates the experience of a few fire fighters during the conflagration. Chief S. C. Despres along with his brother, Arthur, made a narrow escape after a wall collapsed. When the wall of the Rich and Hallberg building fell against the side of Ransom’s store, firefighters Arthur Despres and Dr. Wilhelm were able to escape safely. Meanwhile, S. C. Despres crawled out beneath the wall and even worse C.W. Ashton, who was thrown down by the collapse, had to crawl out through the flames to safety via a narrow opening under burning wall.[87] The Queen City engine, worked by Mr. Fulghum, in conjunction with the water works service worked efficiently and as expected while working to extinguish the fire.[88]

The large fire was not just local news, but other Michigan newspapers reported the fire over the course of November 1896.[89] One account of the fire comes from the Belding Banner (an identical article in the Saline Observer on November 19, 1896), describes that the fire originated in the C. A. Bugbee’s drug store by the explosion of chemicals and reports that the only fatality proven was that of “Edward Newberry, who was sleeping in one of the upper rooms.”[90] The Crawford Avalanche of Grayling, Michigan, reported that a “Fred Newberry...ran back after something and was burned to death.”[91] The Benton Harbor newspaper suggested that seven or more were probably burned to death, in addition to ”Ed Newberry.”[92] However, besides Newberry and his dog, the historical record does not record evidence of additional fatalities.

Thankfully, another downtown Traverse City fire the likes of November 11, 1896, has not taken place for over a century. Still, citizens of Traverse City should probably still remember a piece of advice from 1881-- “take care of your ashes; look out for incipient fires.”[93]

[1] Ancient History Sourcebook: Juvenal: Satire 3 (Latin/English),” Fordham University Sourcebooks Project, accessed October 15, 2024, https://origin-rh.web.fordham.edu/Halsall/ancient/juv-sat3lateng.asp.

[2] Anna Rose Alexander, "The Problem of Fire in the American City, 1750–Present" in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History (September 28, 2020), accessed October 31, 2024, https://oxfordre.com/americanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-875.

[3] Mark Tebeau, Eating Smoke: Fire in Urban America, 1800-1950 (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2003), 125-127.

[4] Grand Traverse Herald, March 22, 1877, 1, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 20, 2024.

[5] "State Firemen’s Association Proceedings of the Twenty-First Annual Convention at Traverse City, Mich., 1895," TADL Local History Collection, 13.

[6] Tebeau, Eating Smoke, 158.

[7] The Morning Record, January 5, 1899, 2, Newspaper Archives.

[8] Traverse City Evening Record, June 6, 1897, 2, Newspaper Archives.

[9] Grand Traverse Herald, March 22, 1877, 2.

[10] Grand Traverse Herald, March 22, 1877, 1.

[11] Grand Traverse Herald, March 22, 1877, 2.

[12] Grand Traverse Herald, March 22, 1877, 2.

[13] Grand Traverse Herald, January 8, 1891, 5, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 20, 2024.

[14] Grand Traverse Herald, May 8, 1890, 5, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 14, 2024.

[15] Grand Traverse Herald, August 11, 1890, 5,

[16] Grand Traverse Herald, June 26, 1890, 5, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 20, 2024; Grand Traverse Herald, August 1 1890- page 5.

[17] Grand Traverse Herald, October 9 1890, 5, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 20, 2024.

[18] Grand Traverse Herald, March 22, 1877, 2.

[19] Grand Traverse Herald, November 14, 1895, 9, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 30, 2024; The registration number and engine specifics are based on Ed Hass, Jack Robrecht, John Orner, and John Peckham, Steam Fire Engines built by American Fire Engine Company (1892-1904) American-LaFrance Fire Engine Company (1904-1917), accessed October 15, 2024, https://www.oocities.org/ahrens_steamers/ahrens_steamers.pdf.

[20] "Traverse City Fire Record and Expense Ledger, 1882-1901," TADL Local History Collection, 22-23.

[21] “Official Proceeding Council of the City of Traverse City, April 7, 1896,” in Council Proceedings of City of Traverse City Oct. 1, 1895 to May 4. 1896.

[22] Amy Barritt, “Steamers Stump Readers for January Mystery,” Grand Traverse Journal (February 1, 2017), accessed October 25, 2024, https://gtjournal.tadl.org/2017/steamers-stump-readers-for-january-mystery/; Historical Marker’s Database, ”The Queen City,” accessed October 25, 2024, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=215912.

[23] Steam Fire Engines built by American Fire Engine Company.

[24] “Official Proceeding Council of the City of Traverse City, November 4, 1895,” in Council Proceedings of City of Traverse City Oct. 1, 1895 to May 4. 1896, 6.

[25] "State Firemen’s Association Proceedings of the Twenty-First Annual Convention at Traverse City, Mich., 1895," TADL Local History Collection, 19-20.

[26] “Official Proceeding Council of the City of Traverse City, Sept 21, 1896,” in Council Proceedings of City of Traverse City, May 1, 1896 to May 1, 1897, 3

[27] “Regular Council meeting, December 20, 1897," in Council Proceedings of City of Traverse City, May 1, 1896 to May 1, 1897, 89-90.

[28] “Regular Council Meeting, March 7, 1898,” in Council Proceedings of the City of Traverse City, May 1, 1897 to May, 1898, 112.

[29] “Regular Council Meeting, March 7, 1898,” 112.

[30] "Traverse City Fire Record," 22-25.

[31] “The plan was to run a wire under front street to Winnie & Stevens Store, thence to the top of their building stretching it over the front street house to the top of the cupola of the herald building from there to the Campbell house windmill tower and there to the church steeple.” Grand Traverse Herald, June 21, 1877, 5, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 24, 2024; Grand Traverse Herald, 28 June 28, 1877, 5, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 18, 2024.

[32] Grand Traverse Herald, June 7, 1883, 6, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 20, 2024, https://digmichnews.cmich.edu/?a=d&d=GrandTraverseGTH18830607-01.1.6&srpos=86&.

[33] "Traverse City Fire Record."

[34] "Traverse City Fire Record."

[35] "Traverse City Fire Record," 2.

[36] "Traverse City Fire Record," 2.

[37] Grand Traverse Herald, May 12 1887, 5, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 20, 2024.

[38] Traverse City Record Eagle, January 27 1899, 1, Newspaper Archive.

[39] Traverse City Morning Record, October 11, 1899, 1, Newspaper Archive

[40] F. E. Walker, Traverse City Directory 1894.

[41] "M.B. Holley, “Fire Alarm Signals” Card," TADL Local History Collection.

[42] Grand Traverse Herald, April 20, 1893, 5, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 20, 2024; F.E. Walker, Traverse City Directory 1894, (1894).

[43] Michigan Western 1884 Directory, Ancestry.com, accessed October 28; Grand Traverse Herald, July 4, 1895, 5, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 28, 2024.

[44] Grand Traverse Herald, June 7, 1894, 4, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 24, 2024.

[45] "Traverse City Fire Record," 150-151.

[46] Traverse City Morning Record, September 7, 1899, 3, Newspaper Archives.

[47] Traverse City Morning Record, October 28, 1900, 7, Newspaper Archives.

[48] Traverse City Evening Record, September 10, 1903, 4, Newspaper Archives.

[49] Grand Traverse Herald, January 5, 1882, 5, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 10, 2024.

[50] Grand Traverse Herald, January 5, 1882, 3.

[51] “Official Proceeding Council of the City of Traverse City, May 25, 1896,” in Council Proceedings of City of Traverse City, May 1, 1896 to May 1, 1897; “Regular Meeting City Council June 7, 1897,” in Council Proceedings of the City of Traverse City, May 1, 1897- May 1, 1898, 20.

[52] “Regular Council Meeting, June 21, 1897,” in Council proceedings of the City of Traverse City, May 1, 1897- May 1, 1898, 27.

[53] “Regular Council meeting, July 19, 1897,” in Council proceedings of the City of Traverse City, May 1, 1897- May 1, 1898, 44.

[54] "State Firemen’s Association Proceedings," 11, 60.

[55] "State Firemen’s Association Proceedings," 20.

[56] Grand Traverse Herald June 27, 1895, 5, Newspaper Archives.

[57] State Firemen’s Association Proceedings, 13-14.

[58] State Firemen’s Association Proceedings, 13-14.

[59] See, "Traverse City Fire Record and Expense Ledger, 1882-1901," 28.

[60] "Traverse City Fire Record," 8, 20, 24.

[61] See, "Traverse City Fire Record," 8, 12, 16, 20.

[62] See, "Traverse City Fire Record and Expense Ledger, 1882-1901," 8, 12.

[63] February 15, 1890. "Traverse City Fire Record," 10-12.

[64] December 13, 1892, November 9, 1895, and July 10, 1895. "Traverse City Fire Record," 16, 20.

[65] February 1, 1896. "Traverse City Fire Record," 22-24

[66] Examples found on January 28, 1896, and May 10, 1896. "Traverse City Fire Record," 22-24.

[67] See "Traverse City Fire Record," 20, 24, 28.

[68] "Traverse City Fire Record," 22- 23.

[69] "Traverse City Fire Record," 24.

[70] "State Firemen’s Association Proceedings," 27.

[71] “Terrible Fire: Fourteen Business Buildings Destroyed,” Grand Traverse Herald.

[72] Grand Traverse Herald, 13 March 1884, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 14, 2024.

[73] "Traverse City Fire Record," 22.

[74] “Terrible Fire: Fourteen Business Buildings Destroyed,” Grand Traverse Herald.

[75] Grand Traverse Herald, 8 January 1891, 5, https://digmichnews.cmich.edu/?a=d&d=GrandTraverseGTH18910108-01.1.5&srpos=601&e=--1880-----en-10-GrandTraverseGTH-601-byDA-img-txIN-Steinberg---------.

[76] Grand Traverse Herald, March 17, 1892, 4, Newspaper Archive; Grand Traverse Herald, July 28, 1892, 5, Newspaper Archive; Steinberg was still installing lights for the stage on May 13, 1892. See, Julius Steinberg Papers Collection, TADL Local History Collection.

[77] “Terrible Fire: Fourteen Business Buildings Destroyed,” Grand Traverse Herald.

[78] Julius Steinberg Papers Collection, TADL Local History Collection.

[79] “Terrible Fire: Fourteen Business Buildings Destroyed,” Grand Traverse Herald, 4.

[80] “Terrible Fire: Fourteen Business Buildings Destroyed,” Grand Traverse Herald, 4.

[81] “Terrible Fire: Fourteen Business Buildings Destroyed,” Grand Traverse Herald, 4.

[82] “Terrible Fire: Fourteen Business Buildings Destroyed,” Grand Traverse Herald, 4.

[83] “Terrible Fire: Fourteen Business Buildings Destroyed,” Grand Traverse Herald, 4.

[84] Potentially also known as "Eric Newberry,” as identified by a gravestone in the Oakwood Cemetery, in the 1st Addition Block 382 Lot 02. See, Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/171872973/eric-newberry: accessed November 4, 2024), memorial page for Eric Newberry (1862–11 Nov 1896), Find a Grave Memorial ID 171872973, citing Oakwood Cemetery, Traverse City, Grand Traverse County, Michigan, USA; Maintained by Jack Franke (contributor 46877368).

[85] “Terrible Fire: Fourteen Business Buildings Destroyed,” Grand Traverse Herald, 4.

[86] “Terrible Fire: Fourteen Business Buildings Destroyed,” Grand Traverse Herald, 4.

[87] “Terrible Fire: Fourteen Business Buildings Destroyed,” Grand Traverse Herald, 4.

[88] “Terrible Fire: Fourteen Business Buildings Destroyed,” Grand Traverse Herald, 4.

[89] The Copper Country Evening News, November 12, 1896, 1, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 28, 2024; Zeeland Expositor, November 20 1896, 7, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 28, 2024; The L'Anse Sentinel, November 21, 1896, 4, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 28, 2024.

[90] Belding Banner, November 19, 1896, 2, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 28, 2024; Saline Observer, November 19, 1896, 6, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 28, 2024.

[91] Crawford Avalanche, November 19, 1896 Pg. 2, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 28, 2024

[92] Benton Harbor Evening News, November 11, 1896, 1, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 28, 2024.

[93] Grand Traverse Herald, June 16, 1881, 3, CMU Clarke Historical Library Digital Michigan Newspapers, accessed October 24, 2024, https://digmichnews.cmich.edu/?a=d&d=GrandTraverseGTH18810616-01.1.3&srpos=65&e=-------en-10-GrandTraverseGTH-61-byDA-img-txIN-%22fire+department%22---------.